Last week, the Australian Competition & Consumer Commission (ACCC) released a draft report on customer loyalty schemes in Australia. The report identified “significant concerns” held by the ACCC surrounding data practices, consumer and competition issues relating to loyalty programs in Australia.

The 107-page draft report is available to the public on the ACCC website.

Before handing down its final recommendations, the ACCC is now engaged in public consultation. Until 3 October 2019, the ACCC is inviting submissions from the public on the findings in relation to loyalty schemes. Following this consultation process, the final report will be published in late 2019. If you wish to make a submission, we would encourage you to do so.

The Australian Frequent Flyer intends to make a public submission to the ACCC inquiry. Our core business is helping Australians to get the most out of loyalty programs, so as an independent and unbiased website, we’re uniquely positioned to comment on some of the key issues presented in the ACCC’s report.

Before we do this, we’re asking for feedback from the AFF community on various issues raised in the draft report. Our comments on issues raised in the draft report are outlined below. All AFF members are welcome to leave their feedback on the dedicated AFF thread for this topic.

Here is our take on the issues raised…

Airlines should be more transparent about carrier charges

In section 3.5.2 of the draft report on loyalty schemes, the ACCC quite rightly points out some of the issues relating to carrier charges on frequent flyer redemption tickets. In many cases, these carrier charges are excessive and represent a real profit for the airline, beyond merely covering expenses.

Carrier charges, unfortunately, have become a standard and largely accepted practice around the world. We accept that these charges exist, however, more transparency about the existence and amount of these carrier charges is required.

Qantas Frequent Flyer does not publish a list of its own carrier charges anywhere. Furthermore, members can only find out what these charges will be on any given route if they complete a “dummy booking” on the Qantas website and they already have enough points in their account to make the booking. Frankly, this is not good enough and makes it very difficult for new members to make an informed decision when choosing a frequent flyer program.

Additionally, it is not always possible for customers to find Classic Flight Reward seats on the Qantas website, which is not always able to quote complex itineraries and does not display award seats originating in many overseas countries.

Australian Frequent Flyer (AFF) has also found examples in the past where the taxes and carrier charges payable on award bookings have been higher than the cost of a commercial ticket on the same flight.

We note that Virgin Australia has not only published a list of its carrier charges online, but anyone can see the taxes & charges associated with Reward Seat bookings when searching for flights on the Virgin Australia website. We consider this to be good practice.

Award flight availability can be very limited

Although it is often frustrating for frequent flyers when they cannot find availability on their choice of flight, we understand that award seat availability is limited. It’s fair enough that seats aren’t always available on every flight, but airlines should at least make an effort to ensure there are a reasonable number of award seats to meet demand. Both Qantas Frequent Flyer and Velocity Frequent Flyer have been aggressively expanding and signing up new members in recent years, but it appears the number of reward seats available may not have kept up. It could be beneficial to consumers if airlines disclosed the total number of seats being made available on each route and class of travel – at the very least, in aggregate.

If reward seats are not being released on certain routes, in certain cabin classes or on certain dates, airlines should disclose this. For example, many Qantas Frequent Flyer members save up their points in the hope of redeeming for a Business ticket to London. But, as we’ve covered previously, Qantas almost never releases Premium Economy or Business reward availability on its Perth-London route. Similarly, Virgin Australia releases barely any Business Reward seats on its flights to Los Angeles more than a week in advance.

It is also worth noting that Bronze and Silver members of the Qantas Frequent Flyer program do not receive equal access to Classic Flight Reward seats in premium cabins on international Qantas flights. Qantas releases some seats to Gold, Platinum and Platinum One members on the initial release date, but only seats that are still unclaimed around two months later are then made accessible to Bronze and Silver members.

Qantas has recently tried to combat public perception of poor redemption availability with Points Planes. We consider this to be little more than a publicity stunt as most of these Points Planes are either positioning flights that would have otherwise flown empty, or simply flights at off-peak times with distressed inventory. This doesn’t solve the fundamental issue of a lack of award seats on routes and times that members want to travel.

It is unfair when loyalty programs unilaterally change the value of members’ existing points

In respect to section 3.5.1, almost every loyalty program in the world has “devalued” members’ points over time by increasing the cost of redemptions. Almost every other week, we hear about another frequent flyer or loyalty program somewhere in the world that has changed its award charts or conversion rates to the detriment of members. For example, Qantas Frequent Flyer will increase the number of points required to redeem for an upgrade or Classic Flight Reward in any premium cabin on 18 September 2019. And American Express devalued Membership Rewards points back in April.

We agree with the ACCC that loyalty schemes unilaterally changing the ‘earn’ or ‘redeem’ rate of points is unfair. This is especially unfair if it affects a member’s existing points balance, to the point where the member would have chosen to accrue points with a different program if they’d been aware there would be a change.

When American Express halved the value of Membership Rewards points for Platinum and Centurion credit card holders earlier this year, they did at least double the existing points balances of some existing cardholders as compensation. This was fair for those whose points were doubled, but not so fair to the many who missed out.

At the very least, loyalty programs should provide ample notice to members when making changes to earn or burn rates. We also feel that loyalty programs should not do this in the middle of a fixed contract term. For example, somebody that has just paid the annual fee on their credit card should expect to be able to continue to earn and redeem points at the advertised rate for the full year that they’ve paid for.

Loyalty programs should do more to inform members when points are due to expire

We don’t have an issue with points expiring, per-se, but loyalty programs need to do a better job of warning members before their points are due to expire. Most loyalty programs say in their terms & conditions that they will undertake to do so, but we have heard of cases involving framing where airlines have hidden these warnings within a monthly newsletter. We can only assume that this is intentional to limit the chance that the member would see the warning. If the member was actually reading each newsletter, then their points would probably not be imminently expiring.

We believe that loyalty programs should, at an absolute minimum, send a dedicated email to members with a subject line along the lines of “Your points will expire in X days”, to give members ample opportunity to keep their accounts active. When logging into your loyalty program account online, you should also clearly be able to see what date your points are due to expire.

Several years ago, Qantas Loyalty boasted in one of its Investor Day Presentations that its breakage rates (the percentage of points that expire unredeemed) were among the lowest in the industry (their goal at the time was <10% breakage). At the time, Qantas was proud of this fact because they said it indicated strong member engagement. However, it seems they’ve had a change of heart because they now make it quite difficult for members to see when their points will expire and, in our view, provide inadequate warnings.

Airlines make it too difficult to determine the booking class

In section 3.3 of the draft report, the ACCC raises several issues relating to earning points with affiliates and booking classes.

AFF has long expressed frustration that none of Australia’s airlines display the booking class on their websites at the time of booking a flight. The booking class makes a significant difference to the number of frequent flyer points and status credits earned, as well as upgrade eligibility and other things.

It is true that many consumers don’t understand booking classes and their implications, but we disagree with the ACCC’s claim that “the booking class is neither hidden nor invisible for those booking tickets online”. Neither Qantas, nor Virgin Australia, displays the booking class online and the only way to find this out is to use a complicated work-around, as outlined in this article. We believe airlines should display the booking class clearly on their websites, so those who want to know this information are able to do so when booking.

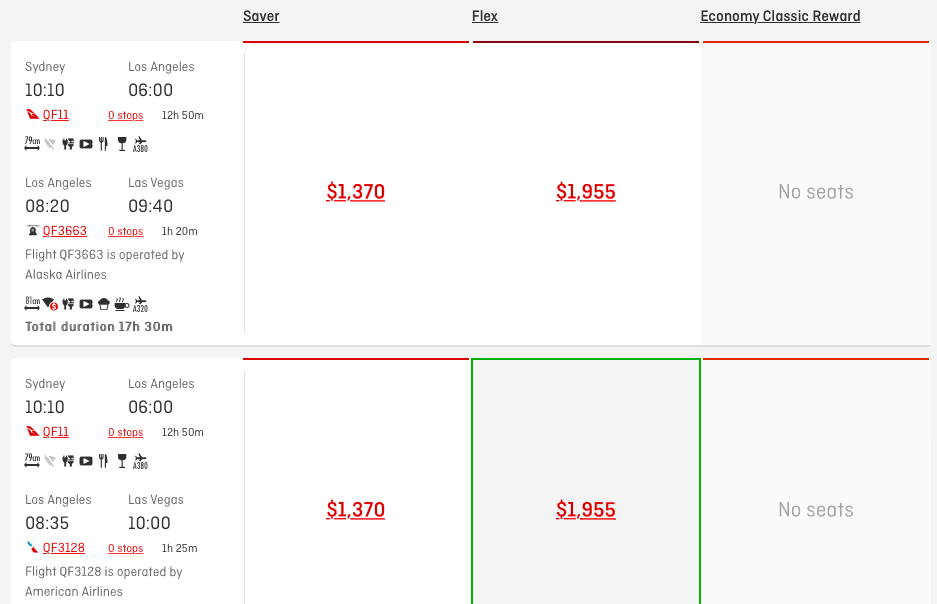

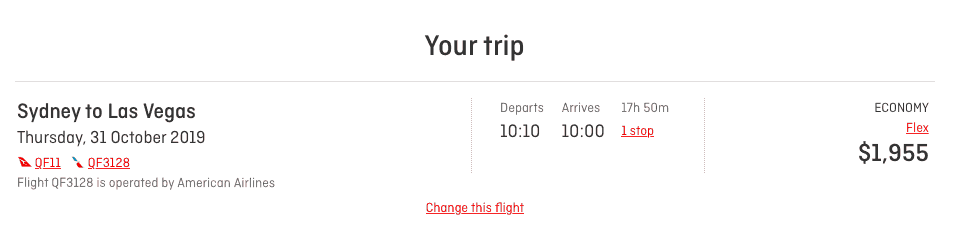

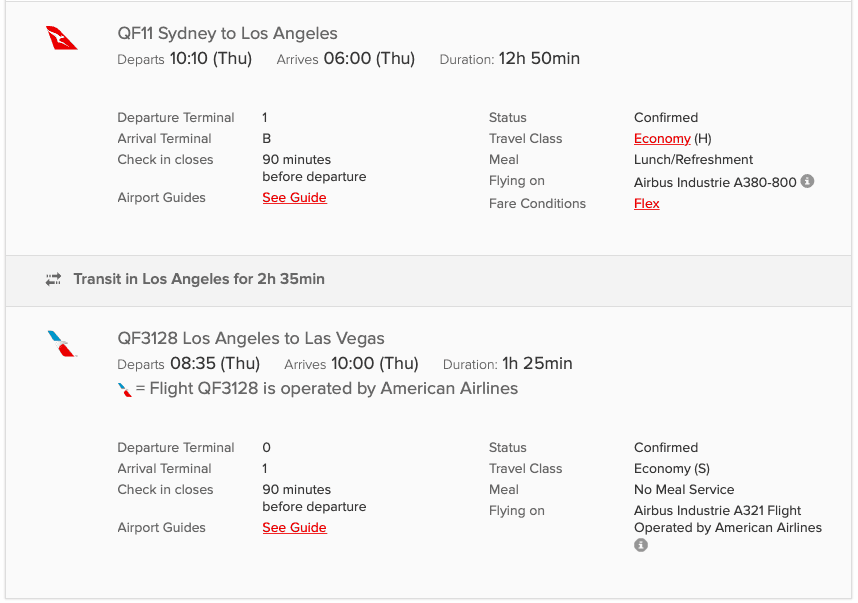

It is particularly important that consumers have access to this information because Qantas routinely sells “Flex” fares on itineraries that include travel on codeshare partner American Airlines, which don’t actually book into Flex fare classes for all flights. After reading a complaint from an AFF member, we investigated and found several examples where this was the case, such as the example in the article linked above with flights from Sydney to Las Vegas:

In this example, a customer would have every reason to believe they were booking a Flex fare class on both the Qantas and American Airlines-operated flights.

Yet, the codeshare flight operated by American Airlines is actually an “S” class fare, which earns fewer points and status credits.

We’ve also found that members of frequent flyer programs are routinely disappointed after inadvertently booking a non-earning fare class when flying on a partner airline. In one example, an AFF member had asked their travel agent to book them onto a Oneworld airline so they could earn Qantas points and status credits. The travel agent booked them a “Q” class fare on Qatar Airways, which is a non-earning fare class with Qantas Frequent Flyer – much to the flyer’s disappointment. Further, Qantas Frequent Flyer members booking Business Class tickets on Malaysia Airlines are often surprised to learn that they will only earn points and status credits at Flexible Economy rates. In these cases, the issue is often a lack of awareness about booking classes and their implications for earning points and status credits.

Supermarket loyalty programs should not collect data from members that don’t scan their loyalty cards

We understand why supermarket loyalty programs collect data when a member scans their loyalty card, and do not fundamentally disagree with the practice. However, most members would not expect data to be collected about their purchases on occasions when they don’t scan their loyalty card. We agree with the ACCC’s view in section 4.5.4 that this practice should end.

We don’t consider frequent flyer programs to be anti-competitive

In section 5 of the draft report on loyalty schemes, the ACCC raises concerns about the broader effect of loyalty schemes on competition.

It is our view that loyalty programs, on the whole, are positive for consumers as they can access real rewards, often for purchases they were likely to make anyway. Indeed, loyalty programs are often used as a means of competing and there is nothing stopping a rival business from starting their own loyalty program.

It is true that airline status tiers can be a factor in preventing customers from switching to another carrier, however airlines can and do offer status matches as a way to remove the “golden handcuffs”. In fact, Qantas regularly offers status challenges to frequent flyers of other airlines as a means of incentivising flyers to switch. There would be nothing preventing another airline from offering something similar.

On page 71 of the draft report, an example is given where regulators in Sweden and Norway banned airline loyalty schemes due to competition concerns. We don’t consider these examples to be relevant to the Australian aviation market where there is already robust competition from multiple carriers. In any case, if we consider the rest of Europe, the current largest airline in Europe by passenger numbers, Ryanair, does not have a loyalty scheme. It is true that airlines in general have high barriers to entry, and we agree with the ACCC’s conclusion that loyalty schemes are not one of the major barriers considering the many other challenges and high costs involved in starting an airline.

Increased personalisation is not necessarily a bad thing

In section 6 of the draft report, the ACCC identifies several emerging issues in the space of loyalty schemes. One of these is the increased personalisation of offers.

This is definitely happening – for example, both Flybuys and Woolworths Rewards send regular, targeted offers to members based on their spending habits. We also believe that Qantas Frequent Flyer is sending targeted deals to members (such as 50% bonus status credits offers) based on members’ website browsing history.

We don’t have a problem with this, and in fact, this allows loyalty programs to send offers which are more relevant and engaging to their members. But consumers should be aware of how their data is being used.

Airlines are employing price discrimination, and it benefits airlines more than consumers

Price discrimination is occurring more and more in the airline industry. In fact, airlines are even investing large amounts of money into technology such as Amadeus Dynamic Pricing to make this easier. Amadeus Dynamic Pricing promises to increase airlines’ revenues by up to 7%.

While data-based price discrimination could benefit some consumers, airlines are ultimately only doing this to increase their profitability. This will leave a majority of consumers worse-off.

If loyalty program members’ data is being used to facilitate price discrimination, we feel that members ought to be made aware of this.

Premium loyalty programs appear to benefit members

We don’t see a problem with premium loyalty programs, as long as members are aware of what they’re paying for.

As an example of a premium loyalty program, Jetstar has been pushing Club Jetstar extensively in recent times. There is a non-refundable annual membership fee which can be paid to access discounted flights. There is no guarantee that members will benefit from discounts throughout the year which are greater than the membership fee paid, however some AFF members say they have benefitted.

Do you agree with our conclusions on the ACCC draft report on loyalty schemes? Share your thoughts on the Australian Frequent Flyer forum: ACCC slams loyalty schemes