Checked Bag Fees Cost US Airlines Millions

In 2008, United Airlines started charging Economy passengers a small fee to check in a second bag on domestic flights. The other US airlines quickly realised that they could increase their revenue by doing the same. Within just months, every legacy carrier in the United States had extended this to charging for the first bag too.

What originally began as a $15 fee quickly became $25, then $30. Most US airlines now charge USD35 for the first checked bag, or USD40 if you pay at the airport.

Even Southwest Airlines, which famously let passengers check up to two bags for free for years, is now starting to charge for checked luggage.

Here’s the thing. Although checked bag fees may be generating extra income for the US airlines, this short-sighted policy could be costing them far more than they earn from it. This policy is also one of the reasons that flying in the United States has become so miserable.

Checked bag fees slow down boarding

Because of checked bag fees, it often seems like passengers in North America are trying to take their kitchen sinks on board as carry-on. The problem is that there’s simply not enough overhead locker space for everyone’s suitcases.

Compared to other countries, the boarding process in the United States takes a ridiculously long time. I’ve been on US domestic flights where boarding has commenced an hour before departure, and we still haven’t managed to get away on time because the cabin crew spent so long trying to find space for – or gate-check – all of the surplus cabin bags.

When bags need to be gate-checked – even if it’s at no cost to the passenger – this wastes the time of airline staff that could be doing other things and has the potential to cause delays. Having bags forcibly gate-checked is also really frustrating for passengers.

And because overhead locker space is such a premium, the boarding procedure for US domestic flights is often an unpleasant scrum. Instead of remaining seated until their boarding group is called, there always seems to be what’s commonly referred to as “gate lice” crowding the boarding area. They’re ready to push their way to the front of the boarding queue at the earliest possible opportunity.

This really detracts from the overall experience. Combined with long queues for airport security, it’s no wonder former United CEO Oscar Munoz once said his passengers were already “pissed at the world” when they stepped onto one of the airline’s planes.

Boarding group madness

American Airlines has just updated its boarding procedure to include 12 different groups. Yes, twelve! This includes nine numbered groups and three “pre-boarding” groups including Concierge Key members, First and Business Class passengers and families with young children.

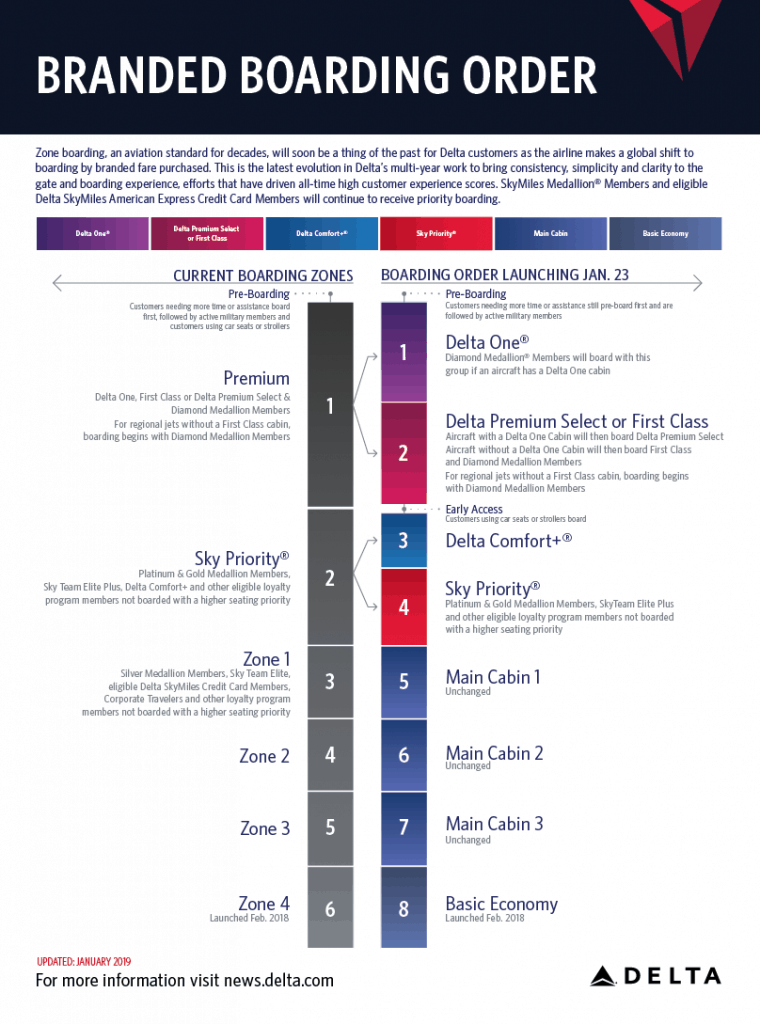

And who remembers the time when Delta “simplified” its boarding procedure by creating a new order with 8 different categories? This didn’t even include those entitled to “pre-board” before Group 1. Nor those entitled to “early access”, who would board between Groups 2 and 3!

This sure makes Qantas’ six boarding groups look simpler and fairer!

A monetisation opportunity

Admittedly, the boarding shambles also creates the opportunity for airlines to monetise the struggle to board first.

Many North American airlines offer priority boarding (which they actually enforce) as a key incentive to earn elite status or get one of the airline’s co-branded credit cards. Some airlines, including Delta, have even tried selling paid subscriptions that get you into a higher boarding group.

Meanwhile, some airlines are now selling reserved overhead bin space for an extra fee.

The major US airlines also try to encourage flyers to pay for more expensive tickets by threatening those on Basic Economy tickets with a spot in the dreaded last boarding group. So, in a perverse way, airlines might actually feel like it benefits them to make the boarding process even worse.

The problem is that boarding a flight in North America now takes way too long. And in the airline industry, time is money!

In Japan, airlines routinely board wide-body aircraft in under 15 minutes. They can do this because most passengers have only a small amount of carry-on and the boarding procedure is orderly and efficient. People simply stand up when their boarding group is called, walk onto the plane and sit down. This is also a much more pleasant experience for passengers!

Looking exclusively at ancillary revenue is short-sighted

Last year, American Airlines made over US$1.2 billion in baggage fees. United and Delta each made a little under US$1 billion, respectively. That’s a lot of money, but it comes at a cost!

Just think of how much extra revenue the US airlines could collect by reducing their turnaround times and increasing aircraft utilisation. I would argue that the increase to airlines’ bottom lines from operating more flights with the same number of aircraft would far outweigh the ancillary revenue earned from checked bag fees.

Looking purely at revenue from checked bag fees also overlooks the big picture. Like, how much revenue have the US legacy carriers lost over the years to airlines without checked bag fees – such as Southwest Airlines?

Unfortunately, now that Southwest Airlines is introducing checked baggage fees too, there aren’t many airlines left that don’t have them. Frankly, I think this is a really poor decision by Southwest as the airline will lose its competitive advantage and lose market share. It will also have to increase aircraft turnaround times or take a big hit to its on-time performance, since so many more passengers will now try to bring carry-on to avoid the checked baggage fees, slowing down boarding.

Shorter turn times = greater aircraft utilisation

When Qantas reduced its standard Boeing 737 turn time from 40 to 35 minutes in 2015, it was able to increase its fleet utilisation by 5%. The efficiency improvements saved Qantas millions, while also allowing the airline to launch new routes without buying any new aircraft.

At American Airlines, for example, the minimum turn time is currently 40-45 minutes (although it’s usually longer than this). By comparison, Southwest Airlines has for years turned planes around in just 30 minutes.

In fact, American Airlines has just started boarding domestic flights five minutes earlier – now up to 40 minutes before departure – to accommodate its new boarding groups.

This could explain why JetBlue once trialled a system in Orlando where passengers could check in their carry-on sized bags for a significantly reduced fee of only $5.

Planes sitting on the ground don’t earn money. So, reducing turnaround times to the international standard would have huge cost and revenue benefits for airlines.

In fact, Southwest Airlines has publicly said that adding even just a couple of minutes to the block time for each flight would mean they’d have to buy 8-10 more planes to maintain their current schedule. (I guess they’ll have to start sourcing those extra planes or cutting their schedule now…)

But it won’t be possible for US airlines to reduce turnaround times until they make the current boarding process quicker. And airlines can’t do that while continuing to charge such high fees for checked baggage.

Community Comments

Loading new replies...

Join the full discussion at the Australian Frequent Flyer →