OK, I know you were probably thinking when you read the headline of this article that nobody wants to see their hard-earned points expire!

I agree with you, but hear me out…

Contents

The different ways points can expire

When airlines first started introducing frequent flyer programs in the 1980s, many used an expiration method known as “time stamping”. This is where points earned at a specific time would expire a fixed amount of time later, unless redeemed first.

Several frequent flyer programs still use time stamping today, including Singapore Airlines KrisFlyer, Emirates Skywards, Air New Zealand Airpoints and Malaysia Airlines Enrich. For example, all KrisFlyer miles expire three years after being earned.

Nowadays, more airlines use activity-based expiration policies. Points don’t expire, as long as you continue earning or redeeming points at least once every year, 18 months, two years or three years.

A few programs add an extra condition, such as Avianca LifeMiles which requires you to earn at least one new mile every 12 months to keep your balance alive. Going a step further, Etihad Guest and Air France/KLM Flying Blue require you to fly at least once every 18 months or two years, respectively.

Some airlines no longer expire points at all

At the other end of the spectrum, several frequent flyer programs no longer expire points or miles at all.

Delta was one of the first major airlines to remove the expiration of miles in 2011. Since then, other airlines have followed including United, Hawaiian Airlines, JetBlue and Virgin Atlantic. These airlines all heavily market the fact their points or miles “never expire”.

Frankly, this is great PR.

But playing devil’s advocate for a moment, is this really such a good thing for frequent flyers in the long run?

Too many points in circulation leads to inflation

One of the reasons that many frequent flyer programs have been increasing the cost of reward flights lately is that the demand for these rewards is outstripping supply. We know this because so many frequent flyers are struggling to find reward seats on flights they want.

There are a few ways that airlines could bridge this gap between supply and demand.

One option would be to sell less points to third parties and limit credit card sign-up offers. This is unlikely to happen because airlines would lose a huge amount of revenue.

Another option would be to release more reward seats. But airlines have been reluctant to do this – at the fixed, low “Classic” reward rates, anyway – because they want to sell as many seats as possible to customers paying cash.

A third option, which most airlines have chosen, is to keep increasing reward seat prices…

As harsh as it sounds, a healthy rate of “breakage” (points that expire unused) does at least reduce the amount of points in circulation. This actually benefits the rest of the program members who go to the effort of ensuring their points don’t expire.

Programs that don’t expire points often expire value instead

There’s one thing that the frequent flyer programs whose points never expire have in common. They all now use dynamic award flight pricing.

In fact, most of these programs no longer even publish award charts that give an indication of how many points or miles you might need for a redemption. And they’re among the biggest culprits in the industry when it comes to no-notice devaluations.

Ultimately, with these programs, reward flight pricing is now unpredictable and often much more expensive than before.

Unredeemed points represent an accounting liability for loyalty programs. If points never expire, airlines can’t rely on breakage to naturally reduce this liability. Instead, the temptation is to lower the internal valuation of existing points, or make the points harder to use so that some will just remain unused forever (even if they don’t technically expire).

I’m not saying it’s fair for loyalty programs to reduce the value of existing points without informing their members. But the reality is that many have done this, and some of the biggest culprits have points that never expire.

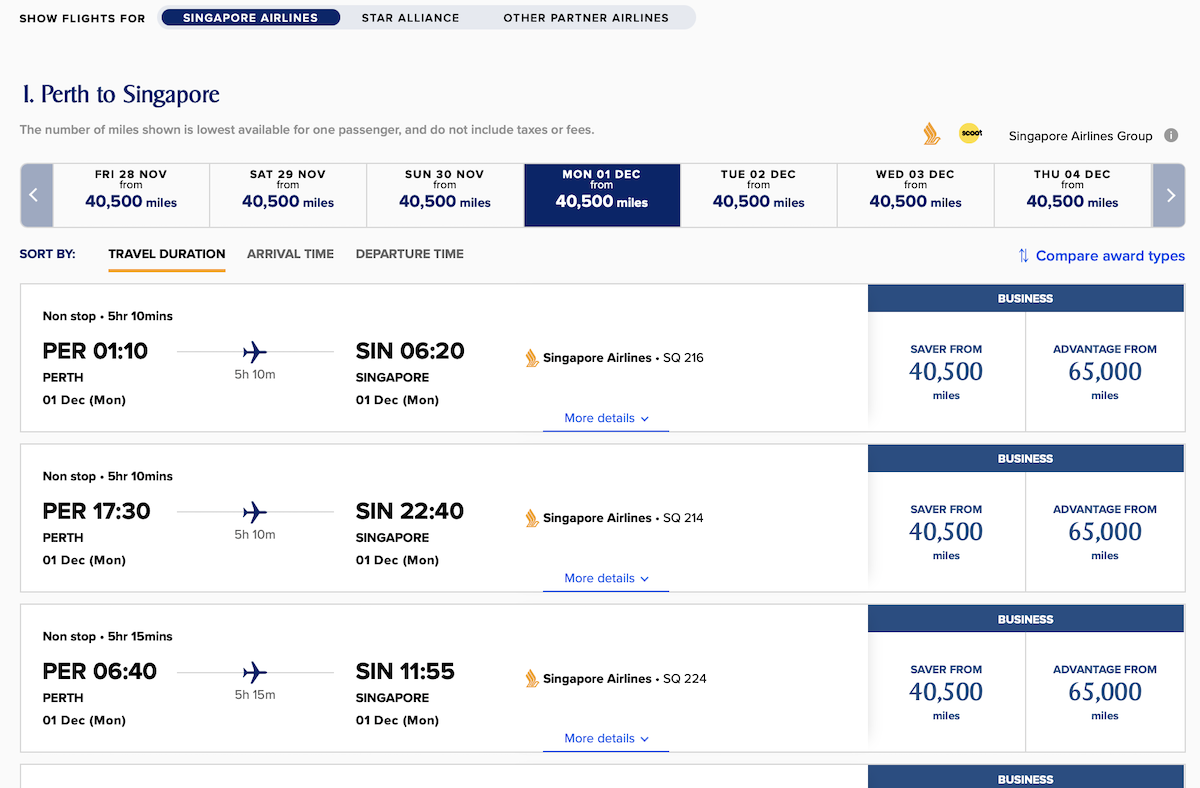

Better reward flight availability

Regardless of what you might think about KrisFlyer’s time stamping policy for expiring miles, Singapore Airlines has pretty good Business Class award availability and pricing. Singapore Airlines can afford to be more generous because it accounts for a relatively high expected breakage rate as part of its program design.

If KrisFlyer decided tomorrow that its miles would no longer expire, the program would almost certainly need to “adjust” its award pricing and availability to compensate for the expected increase in miles that would be sitting in members’ accounts.

It’s reasonable for loyalty programs to incentivise engagement

Ultimately, I think it’s reasonable that you should need to engage with a loyalty program – by earning or redeeming at least one point every now and again – to stop your points from expiring.

However, I say this with a few caveats:

- Airlines should make it easy to earn and use points, including by offering some easy options to people who may not live in the airline’s home country.

- Airlines should give plenty of notice before points expire. And I mean proper notice, like an email that clearly states “Your points will expire in 3 months” in the subject line – not something buried at the bottom of a newsletter that the person probably won’t read.

In any case, you should be redeeming your points as soon as possible anyway! Frequent flyer points don’t earn interest and ultimately become less valuable over time.

If the threat of imminent expiry actually encourages people to use their points, rather than hoarding them, that might not actually be such a bad thing. Assuming those points don’t just get cashed out for a toaster out of frustration.

Time stamping is probably a bit too harsh

I think a policy where points only expire after several years of complete account inactivity is reasonable.

But there are several reasons why airlines shouldn’t have expiration policies that are too harsh. In particular, there are some large downsides to the “time stamping” policies used by the likes of Emirates or Singapore Airlines:

- It’s unfair to occasional flyers without access to credit cards who may not be able to save up enough points or miles within 3 years to ever redeem a meaningful reward.

- It incentives people not to directly earn points with that program, but to instead collect points with a flexible points program (such as a credit card scheme) and only transfer points in when needed. Ultimately this is actually better for most consumers, but it’s not what the airline wants you to do.

Personally, I stopped engaging with the Etihad Guest program last year after it made a range of member-unfriendly changes, including to the way miles expire. Etihad’s new policy is so punitive that it’s actually backfired for them, in this case.

There should be a way to get your expired points back

Occasionally, people do have legitimate reasons for letting points expire due to inactivity. Often, it’s simply because they forgot about the points or didn’t realise they would soon expire, and the airline (surprise, surprise) went to little or no effort to alert the member before it was too late.

But sometimes people might be preoccupied with health issues, the birth of a child, a work assignment, or any number of other things that are frankly much more important than managing a loyalty program account.

When people do let their points expire, I think it’s only fair if loyalty programs provide some sort of way to get some or all of them back. This could be in the form of a challenge – such as the Qantas points reinstatement challenge, or could even be for a small fee. That way, the airline doesn’t risk losing all goodwill if a member suddenly realises all the points they’d saved up are gone.

What’s your take?

So, over to the AFF community! What do you think?

Should points be allowed to expire under some circumstances? Or do you prefer a program where points never expire?

You can share your thoughts on the Australian Frequent Flyer forum…

Community Comments

Loading new replies...

Join the full discussion at the Australian Frequent Flyer →