So lets do the numbers on the distortion caused by the 'working of the system in Europe.

Drax expects to burn about seven million tons of wood annually and collect about $600 million a year from renewable-energy credits.

So they are getting $600m back (from tax payers) because they are burning wood that would be illegal to burn if sourced in most of Europe but as it is coming from the US (with much weaker environmental protection) which allows clear felling of old growth forests it is OK. The cost of 7 million tons of thermal coal (using year avg prices) was $430m.

All of a sudden it makes it easy to see where the funding for pushing these Green Initiatives may be coming from! And curiously enough the provable science does not support this so-called Green Initiative - what a surprise!

So by burning trees that took 30, 40 or over 100 years to sequester their carbon and releasing it in a few minutes is OK. Unless an area 30-100 times the size is replanted for each area cut down then it is increasing carbon emissions.

BUT fresh water is also a valuable commodity, as is arable land that is needed for food production - so the model does not work. Isn't this hypocritical then to criticise the developing economies for doing the same thing? Such as in Malaysia, Indonesia, Brazil and Argentina? Yes, the UK carbon tax is working well.

[h=1]Europe's Green-Fuel Search Turns to America's Forests[/h]INDSOR, N.C.—Loggers here are clear-cutting a wetland forest with decades-old trees.

The U.S. logging industry is seeing a rejuvenation, thanks in part of Europe's efforts to seek out green fuel and move away from coal. Ianthe Dugan explains. Photo: Getty Images.

Behind the move: an environmental push.

The push isn't in North Carolina but in Europe, where governments are trying to reduce fossil-fuel use and carbon-dioxide emissions. Under pressure, some of the Continent's coal-burning power plants are switching to wood.

But Europe doesn't have enough forests to chop for fuel, and in those it does have, many restrictions apply.

So Europe's power plants are devouring wood from the U.S., where forests are bigger and restrictions fewer.

This dynamic is bringing jobs to some American communities hard hit by mill closures. It is also upsetting conservationists, who say cutting forests for power is hardly an environmental plus.

On a hot Tuesday along North Carolina's Roanoke River, crews were cutting the trees in a swampy 81-acre parcel, including towering tupelos. While many of the trunks went for lumber, the limbs and the smaller trees were loaded on trucks headed to a mill 30 miles away, to be ground up, compressed into pellets and put on ships to Europe.

"The logging industry around here was dead a few years ago," said Paul Burby, owner of a firm called Carolina East Forest Products that hired subcontractors to cut the trees after paying a landowner for rights. "Now that Europe is using all these pellets, we can barely keep up."

The logging is perfectly legal in North Carolina and generally so elsewhere in the U.S. South. In much of Europe, it wouldn't be.

The U.K., for example, requires loggers to get permits for any large-scale tree-cutting. They must leave buffers of standing trees along wetlands, and they generally can't clear-cut wetlands unless the purpose is to restore habitat that was altered by tree planting, said a spokesman for the U.K. Forestry Commission.

Italy and Lithuania make some areas off-limits for clear-cutting, meaning cutting all of the trees in an area rather than selectively taking the mature ones. Switzerland and Slovenia completely prohibit clear-cutting.

It is a common logging practice in the U.S.

U.S. wood thus allows EU countries to skirt Europe's environmental rules on logging but meet its environmental rules on energy.

The wood-power industry says its approach is environmentally sound. "We only take the low-value material from the forest," said Nigel Burdett, the environment chief for Drax PLC, a U.K. power company that is converting some coal units at the U.K.'s biggest power plant to wood and setting up pellet mills in the U.S.

The industry also cites the ability of trees newly planted after cutting to absorb greenhouse gases. "Young trees absorb more carbon than older trees," said John Keppler, chief executive of the U.S.'s biggest wood-pellet exporter, Enviva LP, at a London conference on "biomass" power in April. "What's the best way to get more carbon absorbed? Cut it down. Replant."

Environmental groups dispute that logic. They say all the carbon that mature trees have been "sequestering" is instantly released when they are burned, far more rapidly than saplings can absorb it.

If Europe's goal is to reduce carbon emissions, "it doesn't make any sense to cut down the trees that are sequestering carbon," said Debbie Hammel, a resource specialist at the Natural Resources Defense Council.

Enlarge Image

Parts of some trees cut in the U.S. become fuel for Europe's power producers, processed into wood pellets. Matt Eich for The Wall Street Journal

The European Union's environment agency said it is trying to assess the consequences of creating a U.S. pellet boom. "The European Commission is currently analyzing the environmental risks" of large-scale biomass production, said a spokeswoman for the office of the energy commissioner at the Commission, which is the EU's executive body.

The Commission, she said by email, is trying to determine "whether such risks can be effectively managed through existing forest/environmental policies."

The push began in 2007, when the Commission set a goal, by 2020, of reducing Europe's greenhouse-gas emissions to 20% below their 1990 level. It also set a goal of moving Europe to 20% renewable energy by 2020.

Solar and wind couldn't meet the latter goal, policy makers recognized. They said wood qualified as a renewable energy source as long as it came from forests that would grow back. Emissions from burning wood contain less of certain chemicals, such as sulfur, than coal smoke.

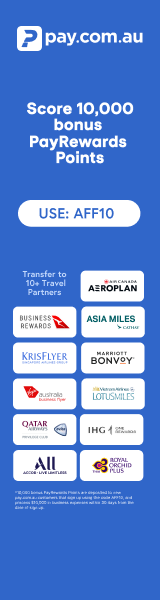

European countries devised a system of awarding credits to companies that generate electricity from renewable sources. They then can sell their credits to electricity suppliers.

Drax has long burned coal in a plant rising from pastoral Yorkshire fields. This has become an increasingly unattractive practice, for a variety of reasons that include a carbon tax floor the U.K. made effective this year. Drax has set out to convert half its coal units to wood.

The plant has converted one of its six units so far, and last year it sold about $90 million of renewable-energy credits to other companies, a spokeswoman said. After it fully converts two more units,

Drax expects to burn about seven million tons of wood annually and collect about $600 million a year from renewable-energy credits.

On a recent day, workers were finishing two giant concrete domes to store pellets, which arrive from ports on Drax's own rail line. "The vast majority" come from the U.S., Drax said.

“ 'The logging industry around here was dead,' said one logger. Now, with Europe's demand, 'we can barely keep up.' ”

Reasons for favoring the U.S., besides its ample forests close to ports, include political pressure in Europe against buying in countries where there would be a risk of getting illegally harvested tropical hardwoods.

Europe's nine largest wood-burning utilities consumed 6.7 million tons of wood pellets in 2012, according to Argus Media, which tracks the industry. Argus expects European pellet consumption to nearly double by 2020, with much of the new demand met from the U.S. American mills exported 1.9 million tons of pellets last year, up nearly fourfold in three years, by Argus's figures.

U.S. exports of coal to Europe have also risen, owing partly to price fluctuations in natural gas. Energy analysts call the trend temporary since some coal plants are set to close in coming years.

The pellet economy appears to be developing faster than rules to guide it.

Principles the EU has told member countries to follow say wood for energy can't come from forests that aren't reforested after cutting. Also, trees from sensitive areas like wetlands, old-growth forests or areas of wide biodiversity aren't supposed to be burned for power. Doing so would violate sustainability criteria the European Commission has outlined, said the spokeswoman for the commission's office of the energy commissioner.

Those criteria were set for biofuels such as alcohol distilled from wood. The EU has told member countries to use the same guidelines in forming their policies on wood as fuel, though this currently isn't binding on them. The EU is currently studying wood-specific rules. Individual countries will be responsible for interpreting and enforcing them, said people involved in the policy process.

In the U.K., it still isn't clear exactly what restrictions there ultimately will be on wood from wetlands trees, said the U.K. Department of Conservation and Climate Change. The U.K.'s draft rules indicate it might be permissible to use some such wood if it were determined that logging it didn't permanently change a wetland's ecosystem, a spokeswoman said. European authorities can't mandate what forests in other countries are harvested, only tell European companies what kind of wood fuel will qualify for renewable credits.

With the rules so unsettled, ensuring the forestry is sustainable has been left largely to power companies and pellet suppliers.

Drax said it carefully monitors its supply chain. "We are not taking old-growth forest," said the company's Mr. Burdett. Drax said it requires pellet suppliers to exclude wood from areas that would be permanently deforested or have their ecosystems destroyed.

Many of the pellet-making plants springing up in the U.S.—which include plants planned by Drax and other European power companies—are near pine plantations established long ago partly to serve the now-slumping wood-pulp market.

Enviva charted a different course. The company, backed by New York private-equity firm Riverstone Holdings, put some of its pellet plants near natural hardwood forests that had established loggers and access to ports, but depressed tree-cutting activity because of pulp-mill closures. Enviva, a supplier to Drax, recently opened one of its largest plants so far in Northhampton County, N.C., in the coastal hardwood belt.

Mr. Burby, the logger who bought rights to cut trees along the Roanoke River near Windsor, said that in the past, he would "shovel-log" the swamps—clear-cut them with bulldozer-like vehicles riding on makeshift roads made of trees. He sold the large trunks to lumber mills and smaller stuff to pulp mills.

Enlarge Image

Some of the logging that feeds European demand is done in swamps like in Windsor, N.C. Matt Eich for The Wall Street Journal

In 2009, a paper-company pulp mill he sold to closed. His business fell off steeply, partly because "you couldn't get rid of the hardwood pulpwood." Landowners didn't want big mounds of limbs piling up, and without a market for the pulpwood, it was hard to make a profit.

Now, Enviva's pellet mill in Ahoskie, N.C., has created a new market for pulp-grade wood. Standing on a section of higher ground near the Roanoke, Mr. Burby said the pellet mill made it possible for him to keep his crew working there, cutting the pine, oak, beech and sycamore in the drier sections and the tupelo gum and cypress hardwoods that grow tall in the flooded areas.

"With Enviva opening up, you can justify shovel-logging again," Mr. Burby said.

The North Carolina Forest Service allows logging in wetlands as long as it complies with state laws prohibiting destruction of waterways, said a spokesman, Brian Haines. Among voluntary "best management" practices, the agency urges loggers in its published guidelines to "minimize activity on saturated soils and near waterbodies." In wet areas, the state recommends building roads out of trees as Mr. Burby did, to help keep heavy machines from damaging the wetland.

Enviva said it requires timber suppliers to follow state-recommended best-management practices and sometimes audits logging operations. Customers sometimes inspect Enviva's operations, its spokeswoman said, so it has an incentive to be careful where its wood comes from.

Still, wood from forests with trees more than 100 years old, including some from wetlands, does wind up in pellet plants, according to loggers. In recent months, foresters have clear-cut portions of two such Roanoke River areas and delivered some of the wood to Enviva's mill in Ahoskie, the loggers said.

Logger George Henerson said that earlier this year, he sold Enviva several hundred tons of hardwood that his crew clear-cut from a swamp that hadn't been logged for about 100 years.

"Enviva, now they need wood bad enough that they're paying for some swamp logging," said Mr. Henerson.

Academics who study wetland forests say some of those along the Roanoke are sensitive environments that it may not be possible to clear-cut sustainably. William Conner, a forestry professor at Clemson University, said recent research shows that wetland trees in the Roanoke area regrow slowly after clear-cutting and without the same species mix.

Stanley Riggs, a geologist at East Carolina University, said that besides the animal and plant habitat that mature wetland forests provide, they help prevent flooding. He said clear-cutting them is "destroying a whole ecosystem." A North Carolina group called the Dogwood Alliance, along with the Natural Resources Defense Council, is launching a campaign against pellet mills.

Enviva's spokeswoman said the swamps along the Roanoke were logged sustainably, because the loggers took measures to prevent damaging the ground, such as keeping their bulldozers on a temporary road, and the landowners will let the trees naturally regrow.